Macular Degeneration

What is age-related macular degeneration?

Age-related macular degeneration — also called macular degeneration, AMD or ARMD — is deterioration of the macula, which is the small central area of the retina of the eye that controls visual acuity. The health of the macula determines our ability to read, recognize faces, drive, watch television, use a computer, and perform any other visual task that requires us to see fine detail.

Macular degeneration is the leading cause of vision loss among older Americans, and due to the aging of the U.S. population, the number of people affected by AMD is expected to increase significantly in the years ahead. AMD is most common among the older white population, affecting more than 14 percent of Caucasian Americans age 80 and older. Among Americans age 50 and older, advanced macular degeneration affects 2.1 percent of this group overall, with Caucasian being affected more frequently than African American, non-white Hispanics and other ethnic groups (2.5 percent vs. 0.9 percent).

Age-related macular degeneration symptoms and signs

Age-related macular degeneration usually produces a slow, painless loss of vision. In rare cases, however, vision loss can be sudden. Early signs of vision loss from AMD include shadowy areas in your central vision or unusually fuzzy or distorted vision.

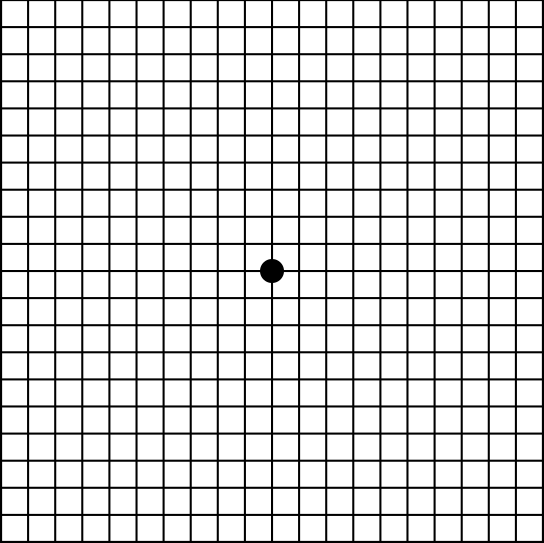

An Amsler grid consists of straight lines, with a reference dot in the center. Someone with macular degeneration may see some of the lines as wavy or blurred, with some dark areas at the center.

Viewing a chart of black lines arranged in a graph pattern (Amsler grid) is one way to tell if you are having these vision problems. See how an Amsler grid works by taking a macular degeneration test. Eye care practitioners often detect early signs of macular degeneration before symptoms occur. Usually this is accomplished through a retinal exam. When macular degeneration is suspected, a brief test using an Amsler grid that measures your central vision may be performed. If your eye doctor detects some defect in your central vision, such as distortion or blurriness, he or she may order a fluorescein angiography to examine the retinal blood vessels surrounding the macula.

What causes macular degeneration?

Though macular degeneration is associated with aging, research suggests there also is a genetic component to the disease. Duke University and other researchers have noted a strong association between development of AMD and presence of a variant of a gene known as complement factor H (CFH). This gene deficiency is associated with almost half of all potentially blinding cases of macular degeneration.

Columbia University Medical Center and other investigators found that variants of another gene, complement factor B, may be involved in development of AMD. Specific variants of one or both of these genes, which play a role in the body’s immune responses, have been found in 74 percent of AMD patients who were studied. Other complement factors also may be associated with an increased risk of macular degeneration.

Other research has shown that oxygen-deprived cells in the retina produce a type of protein called vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), which triggers the growth of new blood vessels in the retina. The normal function of VEGF is to create new blood vessels during embryonic development, after an injury or to bypass blocked blood vessels. But too much VEGF in the eye causes the development of unwanted blood vessels in the retina that easily break open and bleed, damaging the macula and surrounding retina.

Who gets age-related macular degeneration?

Besides affecting older populations, AMD occurs in caucasian and females in particular. The disease also can result as a side effect of some drugs, and it seems to run in families. New evidence strongly suggests smoking is high on the list of risk factors for macular degeneration. Other risk factors for macular degeneration include having a family member with AMD, high blood pressure, lighter eye colour and obesity.

Some researchers believe that over-exposure to sunlight also may be a contributing factor in development of macular degeneration, but this theory has not been proven conclusively. High levels of dietary fat also may be a risk factor for developing AMD.

Commonly named risk factors for developing macular degeneration include:

- Aging. The prevalence of AMD increases with age. In the United States, approximately one in 14 people over the age of 40 has some degree of macular degeneration. For those over 60, the rate is one in eight (12.5 percent); and for seniors over age 80, one in three (33 percent) has AMD.

- Obesity and inactivity. Overweight patients with macular degeneration had more than double the risk of developing advanced forms of macular degeneration compared with people of normal body weight, according to one study reported in Archives of Ophthalmology (June 2003). In the same study, those who performed vigorous activity at least three times weekly reduced their risk of developing advanced AMD, compared with inactive patients.

- Heredity. As stated above, recent studies have found that specific variants of different genes are present in most people who have macular degeneration. Studies of fraternal and identical twins may also demonstrate that heredity is a factor in who develops AMD and how severe it becomes.

- High blood pressure (hypertension). Investigative Ophthalmology and Vision Science reported the results of a European study demonstrating that high blood pressure may be associated with development of macular degeneration (September 2003).

- Smoking. Smoking is a major AMD risk factor and was found in one British study to be directly associated with about 25 percent of AMD cases causing severe vision loss. The British Journal of Ophthalmology in early 2006 also reported study findings showing that people living with a smoker double their risk of developing AMD.

- Lighter eye colour. Because macular degeneration long has been thought to occur more often among Caucasian populations, particularly in people with light skin color and eye color, some researchers theorized that the extra pigment found in darker eyes was a protective factor against development of the eye disease during sun exposure. But no conclusive evidence as yet has linked excessive sun exposure to development of AMD. A small study reported in the British Journal of Ophthalmology (January 2006) found no connection between the eye disease and sun exposure. In fact, the same study found no relation at all between lighter eye color, hair color and AMD. That finding is contradicted by several earlier studies indicating that lighter skin and eyes are associated with a greater prevalence of AMD.

- Drug side effects. Some cases of macular degeneration can be induced from side effects of toxic drugs such as Aralen (chloroquine, an anti-malarial drug) or phenothiazine. Phenothiazine is a class of anti-psychotic drugs, including brand names of Thorazine (chlorpromazine, which also is used to treat nausea, vomiting and persistent hiccups), Mellaril (thioridazine), Prolixin (fluphenazine), Trilafon (perphenazine) and Stelazine (trifluoperazine).

The American Academy of Ophthalmology notes that findings regarding AMD and risk factors have been contradictory, depending on the study. The only risk factors consistently found in studies to be associated with the eye disease are aging and smoking.

How macular degeneration is treated

There is as yet no cure for age-related macular degeneration, but some treatments may delay its progression or even improve vision. Treatments for macular degeneration depend on whether the disease is in its early-stage, dry form or in the more advanced, wet form that can lead to serious vision loss. No FDA-approved treatments exist yet for dry macular degeneration, although nutritional intervention may help prevent its progression to the wet form.

For wet AMD, treatments aimed at stopping abnormal blood vessel growth include FDA-approved drugs called Lucentis, Eylea, Macugen and Visudyne used with Photodynamic Therapy or PDT. Lucentis has been shown to improve vision in a significant number of people with macular degeneration. [For more details, read our article about macular degeneration treatments.]

Nutrition and macular degeneration

Many organizations and independent researchers are conducting studies to determine if dietary modifications can reduce a person’s risk of macular degeneration and vision loss associated with the condition. And some of these studies are revealing positive associations between good nutrition and reduced risk of AMD.

For example, some studies have suggested a diet that includes plenty of salmon and other coldwater fish, which contain high amounts of omega-3 fatty acids, may help prevent AMD or reduce the risk of its progression. Other studies have shown that supplements containing lutein and zeaxanthin increase the density of pigments in the macula that are associated with protecting the eyes from AMD.

Visit and bookmark our Eye Nutrition News page for the latest developments in nutritional research that may prevent or limit vision problems from AMD, cataracts and other eye conditions.

Testing and low vision devices for AMD treatment

Although much progress has been made recently in macular degeneration treatment research, complete recovery of vision lost to AMD is unlikely. Your Optometrist may ask you to check your vision regularly with the Amsler grid described above.

Viewing the Amsler grid separately with each eye helps you monitor your vision loss. The Amsler grid is a very sensitive test and it may reveal central vision problems before your eye doctor sees AMD-related damage to the macula in a routine eye exam. For those who have vision loss from macular degeneration, many low vision devices are available to help with mobility and specific visual tasks.